Rudolf Steiner

"That which secures life from exhaustion lies in the unseen world, deep at the roots of things."

“All knowledge pursued merely for the enrichment of personal learning

and the accumulation of personal treasure leads you away from the path;

but all knowledge pursued for growth to ripeness within the process of

human ennoblement and cosmic development brings you a step forward.”

“If we do not believe within ourselves this deeply rooted feeling that

there is something higher than ourselves, we shall never find the

strength to evolve into something higher."

“Love starts when we push aside our ego and make room for someone else.” ...

“If we do not believe within ourselves this deeply rooted feeling that there is something higher than ourselves, we shall never find the strength to evolve into something higher.”

Rudolf Steiner describes in his autobiography - "The Course of my Life" - how destiny provided him with the tools he needed for his development, thus allowing him to spontaneously fulfill what life wanted from him, by following his own instinct.

EARLY LIFE AND WORK

Born on February 27th, 1861, in what is now Donji Kraljevec, Croatia, Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner became an influential philosopher and educator. Steiner attended school in Austria and was a student at the Vienna University of Technology.

His childhood was spent in the Austrian countryside, where his father was a station master. Writing about his experiences at the age of eight, Steiner said, “... the reality of the spiritual world was as certain to me as that of the physical.”

Recognizing the boy's ability, his father sent him to the Realschule at Wiener Neustadt, and later to the Technical University in Vienna. Here Steiner had to support himself financially, by means of scholarships and tutoring. Although he took part in all the social activities going on around him — in the arts, the sciences, even in politics — he wrote that “much more vital at that time was the need to find an answer to the question: How far is it possible to prove that in human thinking real spirit is the agent?”

He studied philosophy in depth, particularly the writings of Kant, but he did not come across a way of thinking that explained the perception of the spiritual world. Thus Steiner was led to develop a theory of knowledge which arose from his own pursuit of the truth. This emerged from a direct experience of the spiritual nature of thinking.

As a student, Steiner's scientific ability was acknowledged when he was asked to edit Goethe's writings on nature. In Goethe he recognized someone who had been able to perceive the spiritual in nature, even though he had not linked this directly a direct perception of the spirit. Steiner was able to bring a new understanding to Goethe's scientific work through this insight into his perception of nature. Since no existing philosophical theory could take this kind of vision into account, and since Goethe had never explicitly stated explicitly what his philosophy of life was, Steiner filled this need by publishing, in 1886, an introductory book called The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethes World Conception in 1886. His introductions to the several volumes and sections of Goethe's scientific writings (1883–97) have been compiled in the book Goethe the Scientist.

During this time his thoughts about his own philosophy were gradually maturing. In the year 1888 he met Eduard von Hartmann, with whom he had been in correspondence with for a long time. He did not stop at the problem of knowledge, but brought his ideas from this realm into the field of ethics, to help him deal with the problem of human freedom. He wanted to show that morality could be given a solid foundation without basing it upon imposed rules of conduct.

Meanwhile his work of editing had taken him away from his beloved Vienna to Weimar. Here Steiner wrestled with the task of presenting his ideas to the world. His observations of the spiritual had all the exactness of a science, and yet his experience of the reality of ideas was in some ways akin to the mystic's experience. Mysticism presents the intensity of immediate knowledge with conviction, but only deals only with subjective impressions; it fails to deal with the external reality. Science, on the other hand, consists of ideas about the world, even if the ideas are mainly materialistic.

By starting from the spiritual nature of thinking, Steiner was able to form ideas that bear upon the spiritual world in the same way that the ideas of natural science bear upon the physical. Thus he could describe his philosophy as the result of “introspective observation following the methods of Natural Science.”

While working on Goethe's writings, Steiner

produced works of his own, including The Theory of Knowledge Implicit

in Goethe's World Conception (1886) andThe Philosophy of Freedom (1894).

While at Weimar, Steiner wrote two more books, Friedrich Nietzsche, Fighter for Freedom,

inspired by a visit to the elderly philosopher,

and Goethe's Conception of the World (1897),

which completed his work in this field. He then moved to Berlin to take over

the editing of a literary magazine; here he wrote Riddles of Philosophy (1901)

and Mysticism and Modern Thought (1901).

He also embarked on an ever-increasing activity of lecturing. However, his real task lay in deepening his knowledge

of the spiritual world until he could reach the point of publishing the results

of this research.

By 1900, Steiner's interest in spiritual development had led to his involvement

in the German Theosophical Society. In 1912, Steiner stepped away from

Theosophy to set up the Anthroposophical Society.

PHILOSOPHICAL THINKER

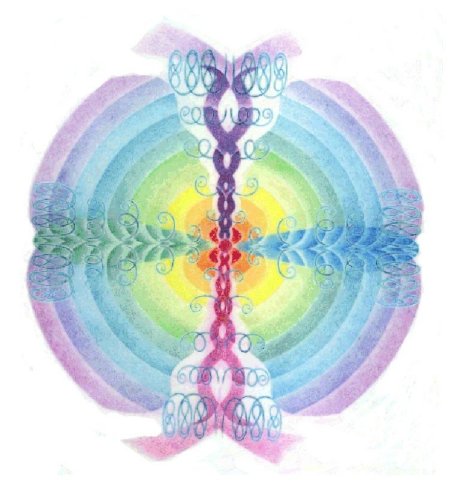

The rest of his life was devoted to building up a complete science of the spirit, to which he gave the name Anthroposophy. Foremost amongst his discoveries was his direct experience of the reality of the Christ, which soon took a central place in his whole teaching. The many books and lectures which he published set forth the magnificent scope of his vision. From 1911 he also turned also to the arts — drama, painting, architecture, eurythmy — showing the creative forming powers that can be drawn from spiritual vision. As a response to the disaster of the 1914–18 war, he showed how the social sphere could be given new life through an insight into the nature of man. His initiative bore practical fruit in the fields of education, agriculture, therapy and medicine.

Anthroposophy is itself a science, firmly based on the results of observation, and is open to investigation by anyone who is prepared to follow the path of development he pioneered. It is a path that begins with the struggle for inner freedom set forth in this book.

Anthroposophy was Rudolf Steiner's own philosophy,

which postulated that heightened consciousness would allow mankind access to

spiritual knowledge. Steiner began construction of the first version of his

Goetheanum, a structure he designed as a center for anthroposophical studies,

in 1913 in Dornach, Switzerland.

Steiner's philosophical interests touched on many different aspects of life,

from the arts to creating supportive environments for people with disabilities.

He is also credited with developing some of the principles of what is now known

as biodynamic farming.

EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHY

In 1919, Steiner established a school for the children of workers at the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory in Stuttgart, Germany. Steiner's educational philosophy encouraged teachers to focus on the physical, emotional and spiritual needs of each student. He also emphasized the importance of creativity in learning.

Steiner's educational approach came to be adopted by many others. Today, there are still are hundreds of schools worldwide using Steiner's methods.

LATER YEARS

With Marie von Sivers, close collaborator and wife, Steiner founded theosophic circles in Germany and abroad.

During his final years, Steiner was criticized by rising political figure Adolf Hitler and plagued by ill health. On March 30th, 1925, Steiner died at the age of 64 in Dornach, Switzerland.

In the 1930s, the socialist government banned Steiner’s books, the German Anthroposophical Society was prohibited and by 1941, the Nazis closed all of Steiner’s Waldorf schools.

Sources:

https://www.biography.com/people/rudolf-steiner-9493564

Michael Wilson, Clent, 1964.